Written by Gwyn Loud for the Lincoln Land Conservation Trust. She welcomes your sightings and questions at 781-259-8690 or gwynloud555@gmail.com.

Very dry conditions continued through September until a Nor’easter arrived on October 12-13. A few “teaser” showers occurred earlier in the past month, but they did not give us any significant rainfall. Dry streams and low ponds told the story. There were many hot days in early October, getting up to the lower 80s, but also some cold nights in the 40s, and the first frost came on October 9, dropping an icy sheen on fields and windshields. In my garden the dahlias, zinnias, and tomatoes succumbed, but flowers near the house still bloom in glory. Climate change is affecting our weather, with climatologists predicting that the Northeast will get more moisture but it will be unevenly distributed through the seasons, leading to an increase in both floods and drought. This is especially challenging for farmers.

Our local fall foliage display seems muted, thanks to the drought conditions, with some leaves falling early, brown and dry. However, a walk in the woods on a sunny day can be a lovely experience of being surrounded by golden leaves – under foot, fluttering down, or on the trees. Supposedly, the peak color in our region will come the last week of October.

Flowers such as New England asters brought color in recent weeks, and in short grass, flowers like lawn daisies and common cat’s ear (aka false dandelions) can still be found. Foliage of plants such as Virginia creeper and poison ivy lend a rich red to the scene, and their berries are eaten by many birds. Seeds and berries abound, including purple pokeweed berries, and windblown seeds such as milkweed and cattail “fluff”. According to naturalist Mary Holland, the brown sausage-shaped “spike of a cattail contains about a million seeds, each of which possesses a silky parachute. Breezes over a one-acre cattail marsh disperse up to a trillion seeds.” If you come across bumpy green spheres the size of small tennis balls on the ground, you are near a black walnut tree. About every three years white pines produce a bumper crop of cones, this being one of those years. Cones litter my driveway and I have watched titmice picking at the seeds in crushed cones. These are female cones and the seeds at the base of each scale are rich in nutrients and proteins, providing winter food for many small mammals and birds. The pines also drop needles each year in the fall, but those needles are about 3 years old, and turn yellow and brown before they drop. New needles grow each year and the newer ones stay on the trees, meaning the tree is an “evergreen.”

In spite of the dry conditions, fungi have been in evidence, including very colorful ones, jack-o-lantern mushrooms. You can guess its color! Beware: it is poisonous and can make you very sick if eaten. As always, never eat mushrooms unless you know for sure it is safe. An interesting flowering plant which lacks chlorophyll, similar to ghost pipes, is pinesap. It is not a fungus but gets its nutrients from fungi in the soil, usually near pine trees. Its fall flowers are usually pink to reddish.

This is garden clean-up season, and I urge residents to avoid being too tidy. Leaving standing stalks in flower beds allows birds to forage for seeds, and for insects to over-winter in stems. Leaves left under trees and shrubs will slowly decompose, enriching the soil. Pick up the rake instead of the leaf-blower! It will give you healthy exercise and avoid the noise and health issues of leaf-blowers.

Some late-fall migrating birds include common grackles, red-winged blackbirds, and rusty blackbirds, with species of sparrows such as Lincoln’s, white-crowned, white-throated, swamp, field, chipping, song, and lots of savannah sparrows still passing through. Ricci field, with plenty of weeds, has been a good spot to see sparrows, and a blue grosbeak and dickcissel were also spotted there. The raptor migration continues and the Fairhaven Bay area has rewarded birders with sightings of bald eagles and osprey. Most of the wood warblers are now farther south but October is when the yellow-rumped warblers (nicknamed “butter-butts” by birders) come our way. Palm warblers have been spotted by several observers, and at Drumlin Farm a yellow-breasted chat was an uncommon and exciting sighting by Mathias Bitter. Many people have been hearing barred owls, as well as great-horned owls. As for water birds, on Flint’s Pond, three double-crested cormorants have been there for weeks and loons have continued to call. Loons, which spend the warm months on fresh water lakes, fly east to overwinter along the coast. Groups of pied-billed grebes, wood ducks, mallards, and Canada geese have been observed on Farrar Pond, and kingfishers have been finding fish.

Every year the Winter Finch Forecast is published in Ontario at this season. Because the seed and cone crop has been poor in much of the Canadian boreal forest this summer, finches and other irruptive species (e.g. red-breasted nuthatches, evening grosbeaks) may head south into New England, where we have a big cone crop. Purple finches have already turned up at Drumlin Farm. The end of October is a good time to set up your bird feeders so that the “locals” get your feeders on their daily routes. A few winter arrivals from points north, such as white-throated sparrows and dark-eyed juncos, have already been seen, but their numbers will grow in the next month and they will happily eat birdseed scattered on the ground. Project Feeder Watch invites those who feed birds to keep records of their feeder visitors and send data to Cornell, contributing to understanding of bird populations and movements. I am about to start participating for the 23rd year and find it has sharpened my observations. See link below if you are interested in joining.

Our local mammals have different strategies for getting through the winter. Woodchucks are true hibernators, and eat to add layers of body fat to get them through the winter as they sleep in their burrows. Other mammals, such as chipmunks, are “nappers”, going into their underground tunnel system where they stash winter food. They nap a lot but wake up periodically to feed on the seeds and nuts they have stored. Will Leona, Conservation Ranger, wrote, “I’ve noticed an uptick in chipmunks making their “clucking” sounds. They are being extra cautious about potential predators as the leaves fall off the trees, and they have less protective cover. That, along with the territorial warnings they exhibit as the competition for foraging ramps up before winter.” Will has also noticed a lot of beaver activity in the past couple of months and the Conservation Department has been busy putting in devices to allow beavers to thrive without causing floods. Many mammals stay active all winter, including gray and red squirrels, deer, and coyotes. I was sad to find a dead river otter on the grass along Weston Rd., without apparent cause of death. Where did it come from? River otters can have a territory of up to thirty square miles so Beaver Pond or streams in Pigeon Hill or Browning Field could easily have been included in its range. Carol Roede’s trail cam has picked up mink, deer, weasel, bobcats, muskrats, otters, much mouse activity at night, and flying squirrels foraging at night and burying acorns. Trail cams have opened a whole new window into wildlife around us in recent years.

Amphibians such as frogs are still active, as cold weather has not set in. I found several tiny wood frogs, about half an inch long near my hose a few weeks ago, and Will Leona reports lots of wood frogs near vernal pools as well as abundant green frogs and pickerel frogs on wetland edges. The red-backed salamander is the commonest terrestrial salamander in New England and this is when they breed, laying clutches of eggs under logs or rocks. Some snapping turtles hatch in the fall from eggs laid in the ground in the spring, while others wait to emerge next spring.

As long as temperatures are mild we still hear an insect chorus. Norm Levey writes, “If the evening is warm there is a roaring chorus of mostly black-horned tree crickets with some narrow-winged and prominently, the jumping bush crickets. Maybe a single snowy tree cricket but they are not abundant. The monotonous scraping of the common true katydids comes from the upper reaches of the oak trees. The stridulations of the aerial crickets become enfeebled by the cold weather except for the ground crickets which can persist into the first weeks of November in the summer warmed earth.” Norm also photographed a Chinese mantis and wrote, “The Chinese mantises are easily spotted now that they have achieved their enormous size. Might be our largest insect, larger than the giant dobsonfly, which is native to the continent. The mantises have a fixed expression like all insects and robotically turn their heads and stare at you and appear to be taking you in. They seem to have intelligence.”

The latest report I have received of a monarch butterfly is from October 7, which is getting late in terms of the migration to the mountains of central Mexico, where it will over-winter. Some dragonflies also migrate, the best known being the common green darner. Michele Grzenda was glad to rescue a shadow darner dragonfly which was trapped in a spider web between a window and the back stairwell at Town Hall. If we see bumblebees, wasps, yellow jackets or hornets at this season, we are probably seeing queens, the only survivors of the colony after workers and drones die. A fertilized queen will hibernate in crevices or in the ground, ready to start a new colony in the spring.

What do spiders do in winter? Some go into diapause, a state where their metabolism slows way down and they don’t eat much. Others die, leaving behind their eggs sacs to hatch next spring, and others seek sheltered spots such as your house garage, or in leaf litter. On Oct. 2 Stacy Carter, Conservation Planner was walking in Upper Browning Field and encountered dozens of orb weaver spiders in their webs.

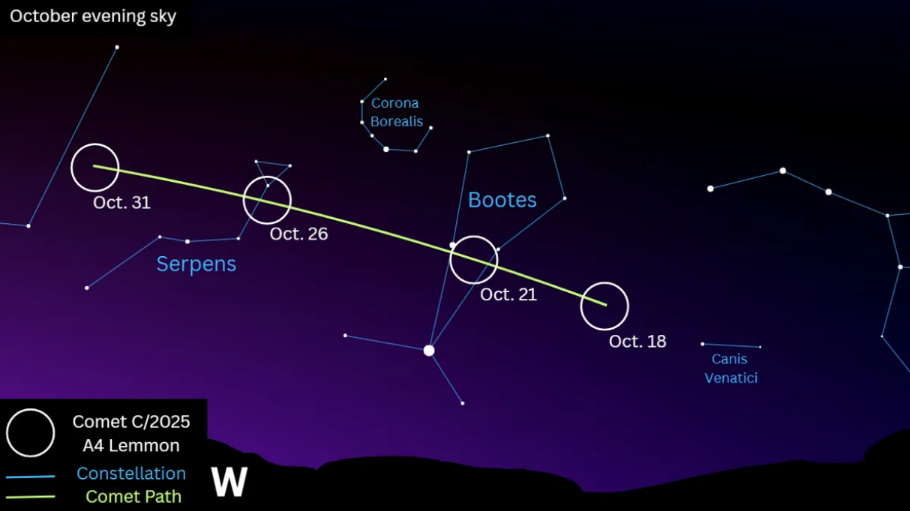

Looking skyward, we have a chance to see comet Lemmon which was discovered by the Mount Lemmon Survey in Arizona on January 3, 2025. Quoting from space.com, “A comet bright enough to be readily visible to the unaided eye comes along usually only once or twice per decade. According to the most optimistic forecasts, at its brightest later this month, comet Lemmon is projected to possibly approach +3 magnitude (such a brightness is comparable to the star Megrez, the star in the Big Dipper that joins the handle with the bowl). So, these upcoming weeks will afford skywatchers an unusual opportunity.”

Links